The Lost City

From Backpacker (January 2019)

Click to read the story.

Trek deep into the heart of the mountains to find an ancient city.

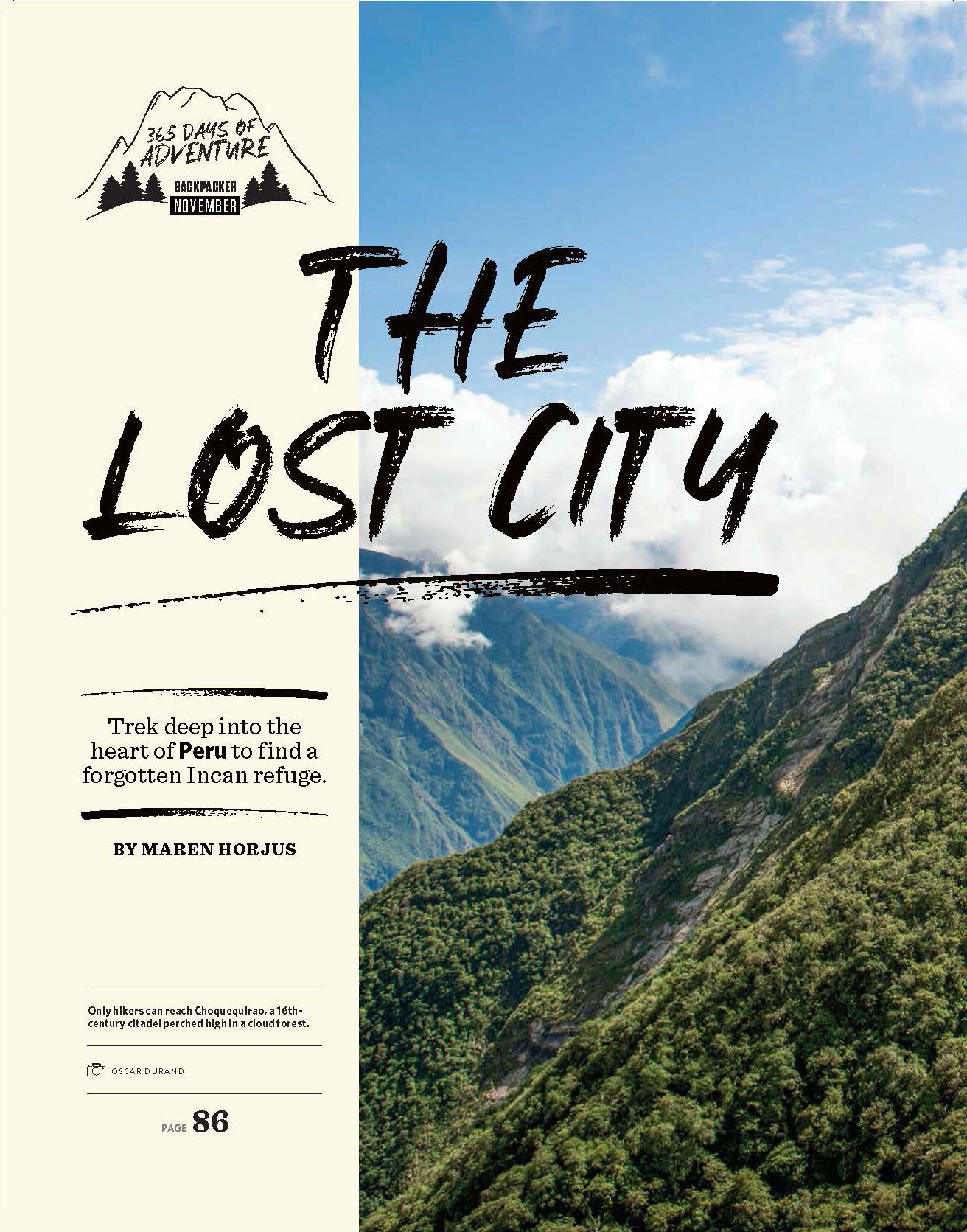

I’ve been hiking for 10 minutes along a wide, dusty track when I turn a corner and the world ends. The red dirt gives way to 5,000 vertical feet of air between me and the teal ribbon of the Río Apurímac, wedged between slopes of broken limestone on one side and jungle across the way. The mountains form a perfect V where the river splits them, like a gunsight straight to the glacier-mantled high peaks of the Andes.

I can feel my heart respond, thumping in my eardrums, and I have to remind myself that I shouldn’t be surprised. Peru sits at the epicenter of contrasting topographies—where the Pacific coast rushes up to meet the western cordillera of the Andes. It results in a tapestry of deserts, plains, rivers, arroyos, jungles, and mountains, 25 of which stand more than 20,000 feet tall, all within an area half as big as Alaska.

On this 40-mile loop, I’ll cross a high desert and dive into a tropical cloud forest at 10,000 feet in the “foothills” of the Andes, steering clear of the big peaks, but always standing in their shadows. And in that seam, hidden in the greenery and tucked behind the ridges and ravines that splinter out from the range, sits an ancient citadel constructed 500 years ago. That’s where I’m headed: perhaps the last refuge of the Incas, just what you’d expect at the end of the world.

The city, Choquequirao, is often heralded as Machu Picchu’s “little sister.” Officially discovered in 1909, lost to time, and rediscovered in the 1960s, it’s as wrapped in mystery and lore as it is tangles of the untamed pepper trees that try to devour it. Most researchers agree that it was commissioned by Pachacuti—the same Incan emperor responsible for Machu Picchu—for religious purposes, their logic basically, Why else would it be so far away from anything else? They have a point: Choquequirao (literally “Cradle of Gold” in the native Quechua language) is a 15-mile walk from Cachora, a teeny village on the outskirts of Cusco, and remains as hard to get to today as it was 500 years ago.

I hike on the same trail the Incas used to reach the citadel in the early- to mid-1500s. It’s also the same path that American archaeologist Hiram Bingham III followed when he found the ancient city in 1909. Choquequirao had been abandoned for more than 300 years at the time, so it probably didn’t look like a ritual worship place or an opulent kingdom, its stone walls and terraces wrapped by the jungle like a squid pulling down a ship. Bingham marked the place on his map, then continued on the ancient Inca Trail until he found something that made him forget all about Choquequirao: Machu Picchu, perched high on a truncated mountaintop and framed by impossibly slender peaks. Excavations began the next year.

The world was instantly smitten. Today, Machu Picchu sees as many as 5,000 people per day, though the site itself is estimated to have housed just 1,000 souls at its most populated. The result? Machu Picchu is literally sinking under the weight of all those footfalls, while pollution is harming the 350 varieties of orchids that paint the surrounding peaks and is expected to affect the already endangered spectacled bear. Despite quotas and price hikes, the world can’t seem to get enough of Machu Picchu.

Meanwhile, Choquequirao fell back off the map until 1968, when Peruvian authorities included it in the Official Register of Archaeological Monuments for the first time. Excavations started in the ’70s, and even today, it’s only an estimated 30-percent restored. Any hiker can reach it, but information is lacking, and the dearth of beta means your best bet is to hire a local guide to show you the way. The guides know a ton about the local culture, flora and fauna, and economy, but, like scholars, historians, and everyone else, even they can only speculate about Choquequirao’s origins and ultimate fall. That means that, without the assist from informational placards, roving tour guides, or interpretive trails, people who visit the place aren’t spoon-fed its history or significance. In Choquequirao, you get to use your imagination.

The edge of the world is not as final as it first appeared. From my aerie overlooking the Andes, the trail crashes 50 stories down to the Río Apurímac on an elevator shaft-steep path. At the bottom, we pass Playa Rosalina, where a few locals raise crops and mules and offer me and my small hiking group tea. It’s 10 miles from Choquequirao and the last reliable water on the way; I can imagine pilgrims stopping here on their way to appointments with the divine. My motivation is different, of course, but there’s something powerful in taking the same path to the same place at such different times. I feel my anticipation for whatever lies beyond this canyon grow with every step.

After Playa Rosalina, we cross the roiling whitewater of the Río Apurímac on a newly installed suspension bridge. On the other side, we have plans to splash in the shallows and spend the night on the riverbank nearby, but the humid, 80°F weather and the prospect of a camp higher—and closer to Choquequirao—propel us onward. So we continue up the other side of the canyon, mules hauling our night’s water and much of our overnight gear.

But mules or not, all pilgrims suffer. Switchbacks decorate the lush north wall, dancing up the mountainside until they disappear into the sky. It feels good to climb out of the oppressive heat, but it’s a grind: There are no campsites between the riverine one we passed and the one we’re gunning for below the ruins, another 5 miles and 5,000 vertical feet ahead. The forest grows thick around the trail, and before long I feel tunnel vision set in. But each time I come across a break in the vegetation—where a mule has chomped away the ferns or scratched its back in the shrubs—I can see the Río Apurímac shrinking.

At the top, the trail follows a ridge that eventually runs past Machu Picchu all the way into the Andes, topping out on 20,574-foot Salkantay. We won’t go that far—we link air-starved meadows popping with red cantuta flowers a few more miles to Marampata, an itty-bitty village built for trekkers on a sheer canyon wall high above the confluence of the Ríos Apurímac and Chunchumayo. There, locals have carved campsites into the grassy slope, like portaledges hanging above the sleepy hamlet. It’s about as civilized as the hike to Choquequirao gets, but as with many international treks, “village camping” is as much a part of the experience as the landscape itself.

And yet for something that seems so inherently part of the trip to Choquequirao, this piece of the journey—and everything that comes before—would be eliminated, or at least irrelevant, if long-term goals to install a tram ever move forward. In 2013, the Peruvian government approved plans for an aerial tramway that would whisk visitors 3 miles from San Ignacio to the main Choquequirao complex, bypassing the trail completely. Fortunately, the project stalled two years later when it got hung up on the rocks of local bureaucracy: The cable car would start and end in different states, and neither side could agree on how to share profits. Though it’s possible they could still break ground on the tramway, my guide, a local, thinks it’s extremely unlikely—or maybe that’s just her wishful thinking.

As with all hikes, much of the power of Choquequirao is in the journey. The prospect of the tram makes me sad, and that night, as I watch the last rays of sunlight on Coisopacana’s snowy summit from my tent, I think about the fall of the city. Like its origin, everything about Choquequirao’s demise is up for speculation, but if the citadel was indeed abandoned in 1573, as many researchers believe, that means it very well could have stood longer than every other major bastion of the Incan rebellion, including Machu Picchu. The Sons of the Sun must have fled the Sacred Valley during the Spanish conquest, heading even deeper into the mountains and jungles to a stronghold where no one could find them, where their way of life would be safe. As the stars pour tiny light onto the terraces and facades around me, I can feel the ancients still here.

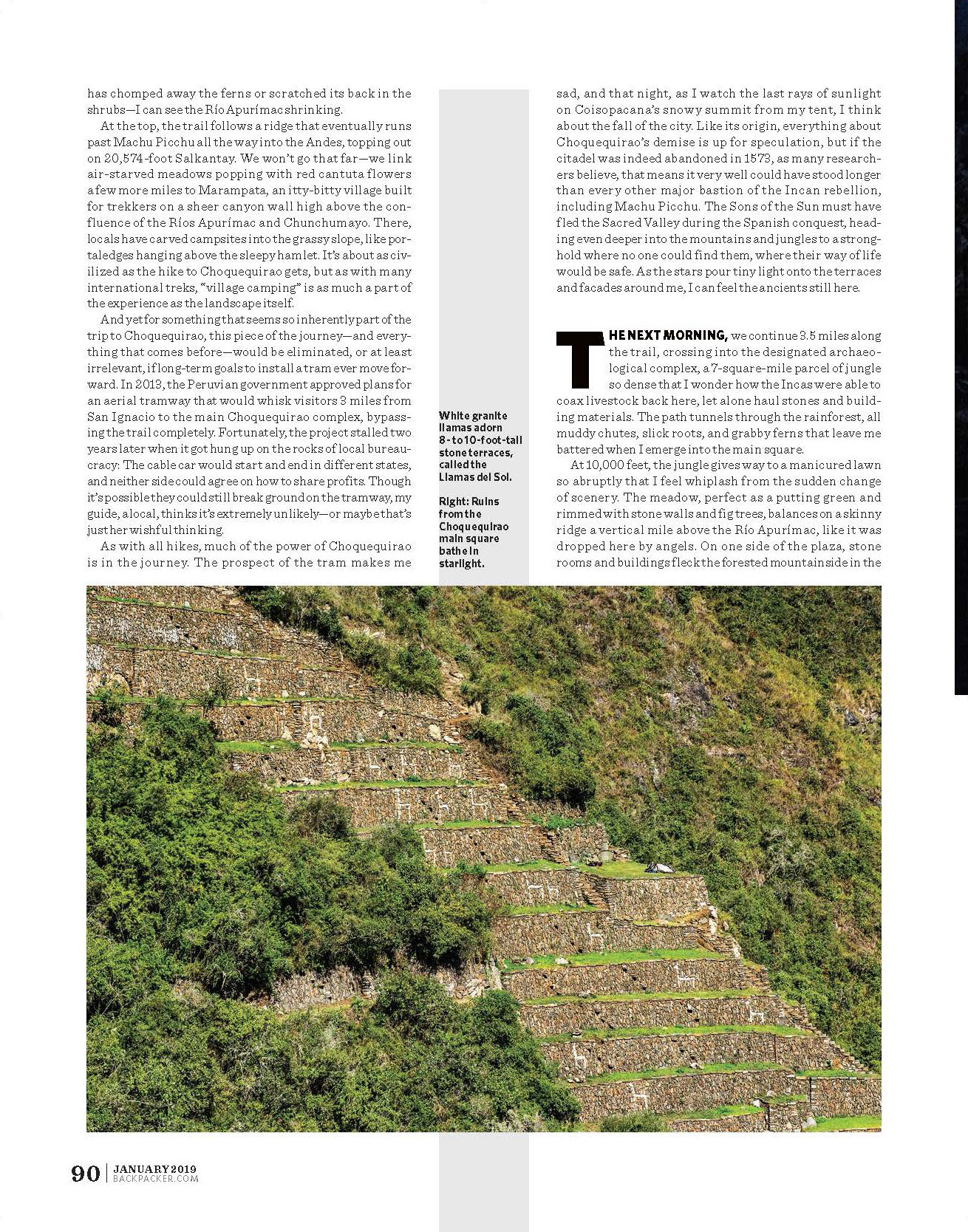

The next morning, we continue 3.5 miles along the trail, crossing into the designated archaeological complex, a 7-square-mile parcel of jungle so dense that I wonder how the Incas were able to coax livestock back here, let alone haul stones and building materials. The path tunnels through the rainforest, all muddy chutes, slick roots, and grabby ferns that leave me battered when I emerge into the main square.

At 10,000 feet, the jungle gives way to a manicured lawn so abruptly that I feel whiplash from the sudden change of scenery. The meadow, perfect as a putting green and rimmed with stone walls and fig trees, balances on a skinny ridge a vertical mile above the Río Apurímac, like it was dropped here by angels. On one side of the plaza, stone rooms and buildings fleck the forested mountainside in the shadow of glaciated summits. On the other, terraces climb a truncated peak, where the ruins of the main temple kiss the heavens. There, another manicured garden framed by broken and crumbly stone walls towers above the one on which I stand. In any other context, I’d think it was a helipad. For now, at least, it’s not.

For now, we have the place to ourselves, save for a party of two. They’re the only other people here beyond the few locals who are working to free the remaining ruins from the cloud forest. So after exploring annexes and buildings off the central plaza, we embrace our solitude and venture down ancient canals to see the Llamas del Sol, where white granite pieces embedded into the gray limestone terraces create the shapes of llamas. They could be a tribute to a sacred creature, a badge of an army hiding in a fortress, or an ostentatious decoration required by a king. This is a place where some things will never be known.

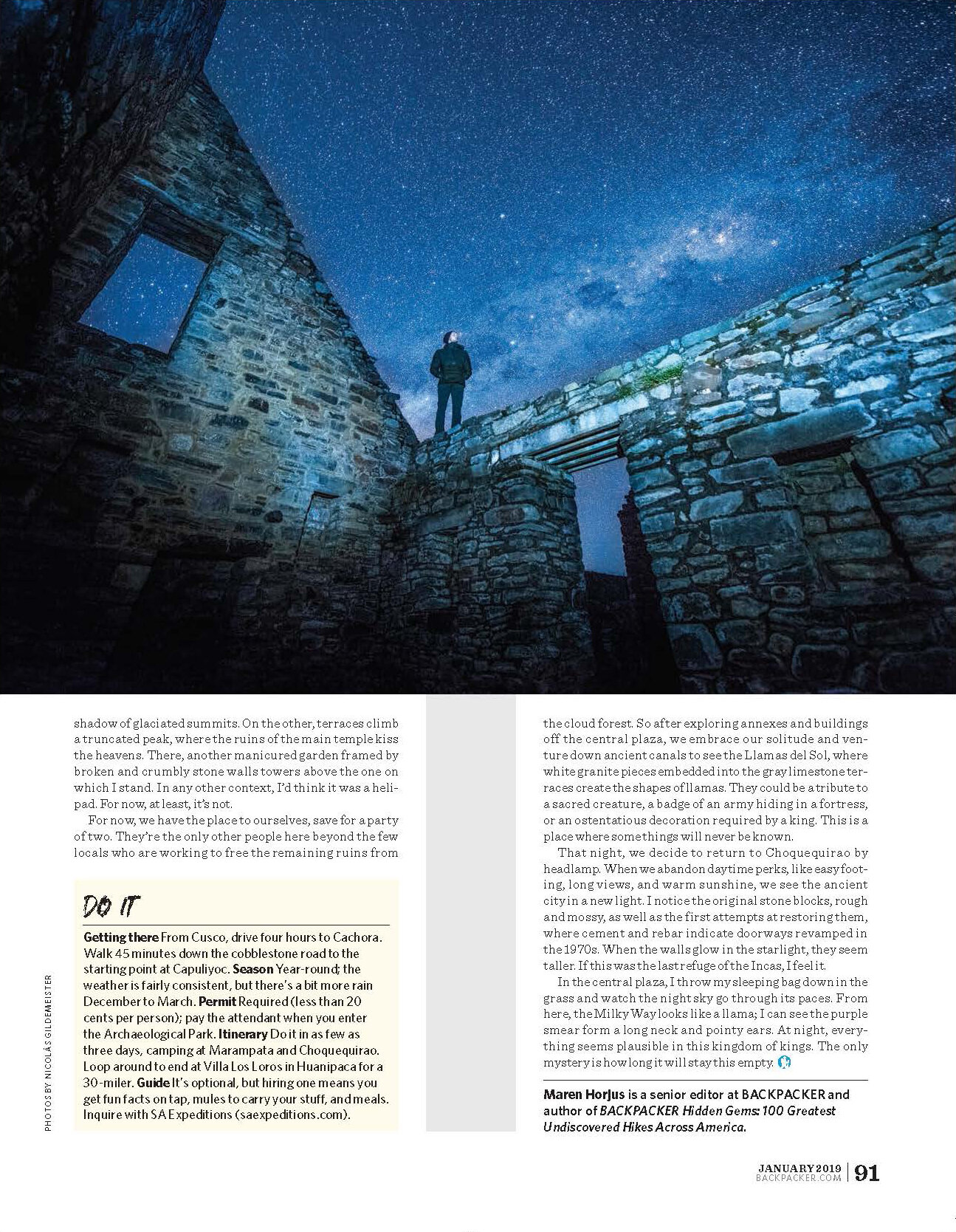

That night, we decide to return to Choquequirao by headlamp. When we abandon daytime perks, like easy footing, long views, and warm sunshine, we see the ancient city in a new light. I notice the original stone blocks, rough and mossy, as well as the first attempts at restoring them, where cement and rebar indicate doorways revamped in the 1970s. When the walls glow in the starlight, they seem taller. If this was the last refuge of the Incas, I feel it.

In the central plaza, I throw my sleeping bag down in the grass and watch the night sky go through its paces. From here, the Milky Way looks like a llama; I can see the purple smear form a long neck and pointy ears. At night, everything seems plausible in this kingdom of kings. The only mystery is how long it will stay this empty.

Maren Horjus is a senior editor at BACKPACKER and author of Hidden Gems: 100 Greatest Undiscovered Hikes Across America.

Do It

Getting there From Cusco, drive four hours to Cachora. Walk 45 minutes down the cobblestone road to the starting point at Capuliyoc. Season Year-round; the weather is fairly consistent, but there’s a bit more rain December to March. Permit Required (less than 20 cents per person); pay the attendant when you enter the Archaeological Park. Itinerary Do it in as few as three days, camping at Marampata and Choquequirao. Loop around to end at Villa Los Loros in Huanipaca for a 30-miler. Guide It’s optional, but hiring one means you get fun facts on tap, mules to carry your stuff, and meals. Inquire with SA Expeditions .